I’ve never really been a lyrics person. The melodies are what bring this boy to the yard. Even tiny moments where a piano puts in a brief appearance thirty seconds from the end of a song or when two voices combine to momentarily melt my innards tend to take precedence over a witty couplet or a heartfelt character assassination. Which is not to say I don’t appreciate fine word-smithery, more that it’s something I gradually acknowledge as the music becomes familiar. Whilst writing about John Grant‘s new album recently, it occurred to me that much of his coruscating honesty had already registered. So, am I paying more attention to artists whose lyrics I know I enjoy, in the same way I try not to listen too carefully to others, or do well-crafted words leap out at you uninvited?

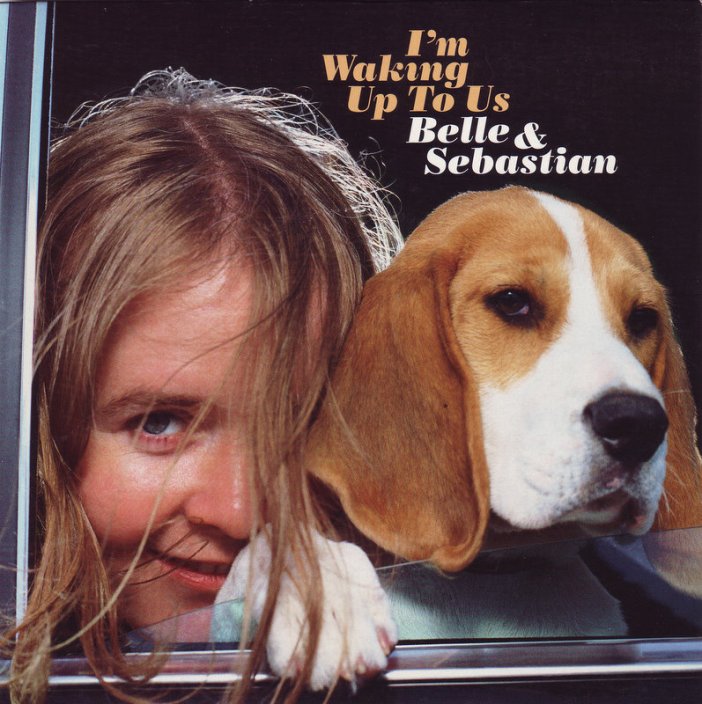

These thoughts were prompted whilst finally reading Paul Whitelaw’s excellent biography of Belle & Sebastian which has unfairly sat on various shelves for several years. The author explores the time when Stuart Murdoch and Isobel Campbell’s relationship hit the skids and the latter prepared for an exit from the band she’d once loved. Having been portrayed as something of a pushover, accommodating Campbell’s numerous whims, Murdoch finally snaps and pours out his angry heart into several brutal lyrics: lyrics to songs on which Campbell actually performs. ‘I’m Waking Up To Us’ juxtaposes a typically jaunty melody with this blunt assessment, “You like yourself and you like men to kiss your arse, expensive clothes; please stop me there. I think I’m waking up to us: we’re a disaster.” I’ve listened to that song plenty of times and noted the acerbic tones in passing, but never before had I really stopped and processed the cumulative sense of bereavement and bitterness in that lyric.

Click the images or scroll down for a Spotify playlist linked to this piece

When a lyric clicks – whether on first or fiftieth play – I tend to cling to a perfectly quotable line or two, keenly anticipating their arrival whenever I hear the song in full thereafter. This, of course, is once again slightly missing the point. The subsequent explanation in ‘I’m Waking Up To Us’ softens the blows somewhat, but for me a well chosen couplet functions much like a musical hook: a euphoric moment in a track which sets my brain alight.

There are plenty of narrative lyrics which hold my attention from start to finish – not least Clarence Carter’s ever wonderful ‘Patches’, to give but one splendid example – but I was raised on a diet of early 90s chart music and then the linguistic pillage that was Britpop. When Rick Witter and Noel Gallagher are foisting their words into your ears, sometimes it’s better to just zone out. Britpop was all about the tunes – most of them stolen – and bellowing out nonsense like “slowly walking down the hall, faster than a cannonball” or “he takes all manner of pills and piles up analyst bills in the country” without any great focus on what the fuck it actually meant. It’s why Jarvis stood out so prominently at the time and the focus was kept largely on the riffs. As an impressionable teenager, I swallowed the Manics’ shtick whole and rather liked the idea of moulding my own sense of my intelligence via their raft of sleeve quotations and passing literary references in interviews. They were my saving grace, my flag in the summit, my band. Looking back now, still very much in love with most of their catalogue, I’m thankfully rather less possessed of a sense of my own self-importance and can see that endless droning about the clever quotation at the end of ‘The Masses Against The Classes’ and the painful need to try and find some merit in the ill-advised of ‘S.Y.M.M.’ was very much of the moment.

This more mature listener can now be found sniggering at pop smashes laced with not especially subtle innuendo. I shared a house whilst at uni with a lad with a slighty unhealthy obsession with Rachel Stevens and can still remember the day he found out about her webbed toes. His ungentlemanly fantasies were never quite the same again, although I suspect they were reignited a few years later when, chasing credibility, headlines and internet chatter, she released ‘I Said Never Again (But Here We Are).’ It doesn’t take a professor of the double entendre to spot the conceit at the heart of this particular lyric, perhaps best exemplified by the demure couplet: “I feel such a traitor, oh I let you in my back door.” Quite. And while I can barely remember more than the odd line of Dylan’s vast and exceptionally worth back catalogue, I am forever blessed with the memory of a member of S Club 7’s paean to anal sex.

I like to think that the various characters responsible for writing many of the nation’s biggest chart hits spend hours daring each other to get ludicrous phrases into their lyrics in the same way we also used to offer a quid to anyone who could manoeuvre fatuous pairings like ‘irate penguin’ into history essays*. Where else could things like ‘let’s go, Eskimo’ come from? Indeed, Girls Aloud deserve a special mention at this point. I loved almost all of their singles as a result of them being utterly and irresistibly catchy, but the lyrics were all over the place. The Rachel Stevens award for pop music traitordom went to ‘Something Kinda Ooooh’ for ‘“Something kinda ooooh, bumpin’ in the back room,” whilst recent best of filler, ‘Beautiful Cause You Love Me’ contained one of the most unintentionally hilarious couplets ever to make the charts: “Standin’ over the basin, I’ve been washin’ my face in.” Oh yes! Still, isn’t it funny how I’m so willing to make excuses for that, raising an eyebrow and proffering a wry smirk, but get my critical arsenal out for the likes of Shed Seven and the Stereophonics?

It’s possible that I draw a line somewhere between brash pop music and the notional integrity of indie rock, but even writing that makes me think that’s quite a pathetic standpoint to occupy. And, frankly, those two bands are very easy targets. I did own a few Sheds singles at one point but quickly grew tired of lyrics like: “She left me with no hope, it’s all gone up in smoke. She didn’t invite me, rode off with a donkey.” Truly, what the fuck is that all about? But is it any different to talk of Eskimos or pushing the button? Some bands even make a virtue of their lyrics being woefully undercooked, Kelly Jones seeming quite happy to dish up baffling non sequiturs for a bit of rawk gravel every couple of years. For recent comeback merchants Suede, it seemed that petroleum and gasoline were never far from Brett Anderson’s lyric book.

During their first reinvention, the band released the glorious ‘Beautiful Ones’, which kept Shell happy and managed a burst of imagery which might go down well with Rachel Stevens’ team of writers: “high on diesel and gasoline psycho for drum machine, shaking their bits to the hits.” The true nadir came during the utterly off their tits phase of ‘Head Music’ and ‘She’s In Fashion’ with the profound couplet “and she’s the taste of gasoline, and she’s as similar as you can get to the shape of a cigarette.” Everyone knew those lyrics were shit, but everyone nodded along and enjoyed the tunes. Suede would be mocked mercilessly for such slap-dash songwriting in the same piece as being awarded Single Of The Week. It’s just what they do, you see. ‘Bloodsports’ would suggest that things haven’t changed too much during the cleaner years.

But what of the bands almost immune from criticism, revered at every turn and held aloft as artists of a generation? Clearly, Radiohead have come out with some very peculiar lyrics over the years but I took as my example one of my absolute favourite songs of theirs, ‘Weird Fishes / Arpeggi’. I love it, as I’ve explained at length elsewhere, particularly because of the vocal interplay in the third verse. Couldn’t give the most minute of shits what is being said, I just go all wobbly when that moment hits. EVERY. SINGLE. TIME. And what of the song’s lyrics? “I get eaten by the worms and weird fishes,” is neither especially good nor especially bad, but in the track itself Thom is doing his level best to use his vocal as simply another instrument anyway. Straight out of the Michael Stipe school of art-rock mumbling and in no way detrimental to the power of the song.

But look back at old school folders and you’ll see band logos and fragments of lyrics all over the place. Do they matter more at that age? Is our increasing exposure to pretty much anything ever made as soon as we want it robbing us of the opportunity to absorb the true heart of the songs we hear? The feeling of being blindsided by a great bit of writing is still one of joyous intensity, whatever the frequency. I can still remember listening to ‘Karen’ by The National and thinking, ‘hang on a minute. What did he just sing?’ at the lyric, “It’s a common fetish for a doting man, to ballerina on the coffee table, cock in hand.” How’s that for imagery, tutu jumpers and back door monitors?

Just as the whole ‘but what does it really mean?’ question at school nearly put me off poetry for life, I increasingly realise that I don’t need to understand what they’re on about, preferring to simply bask in the occasional majesty that nonchalantly drifts out of the speakers. Whether it’s new stuff like Martin Rossiter’s ‘I Must Be Jesus’ – “If life’s unkind, then you must be divine. And, yes, I do mean literally” – or the returning triumph of an old friend – “Oh, I didn’t realise that you wrote poetry. I didn’t realise you wrote such bloody awful poetry, Mr. Shankly” – I rather like not looking too hard. If it takes a rock biog to finally make me realise that something clever has been going on under my nose without me ever noticing, then so be it. The alchemy of great songwriting is way out of my reach and, while I’m never shy about casting the first (or second or third) stone when critiquing a record, I’ll always keep listening with the hope and expectation that I will find something truly magical. No problem so far.

*E.g. Disraeli was left, like an irate penguin, snubbed by Peel despite Gladstone’s appointment to the government